Mira Nair has spent over three decades redefining what Indian cinema can be on the global stage. Born on October 15, 1957, in Rourkela, Odisha, she's transformed from a theater performer at Harvard into one of the world's most celebrated independent filmmakers. Her films have won Golden Lions at Venice, premiered at Cannes, and earned Academy Award nominations—but what truly sets her apart is her relentless commitment to telling the stories that mainstream cinema ignores.

She's the filmmaker who put street children from Mumbai on screen with raw authenticity. She's the director who celebrated Punjabi weddings with infectious joy. And she's the activist-philanthropist who bet her career earnings on changing the lives of thousands of disadvantaged youth. Whether you're familiar with her masterpieces or discovering her legacy through her son Zohran Mamdani's historic election as New York's first Muslim mayor, Mira Nair's influence on global cinema and social change is undeniable.

From Theater Dreams to Documentary Reality

The path to becoming a visionary filmmaker wasn't straightforward. After moving from Odisha to Delhi at age eleven, Nair attended boarding school in Shimla, where she fell in love with English literature. She later studied sociology at Miranda House, Delhi University, earning a full scholarship to Harvard—where she chose the American institution over Cambridge to study in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

At Harvard, Nair discovered theater. She performed in plays written by Bengali dramatist Badal Sircar and won the prestigious Boylston Prize for her performance of Jocasta's speech from Seneca's Oedipus. But theater was just the beginning. It was in the film program where she found her true calling.

Her early documentaries revealed her distinctive voice: gritty, intimate, and unapologetically focused on the margins of society. Jama Masjid Street Journal (1979) captured the lives of Muslims in Old Delhi. India Cabaret (1985) explored the nightlife and stories of women working in Mumbai clubs. These weren't glamorous documentaries—they were unflinching portraits of overlooked communities.

The Breakthrough: Salaam Bombay! That Changed Everything

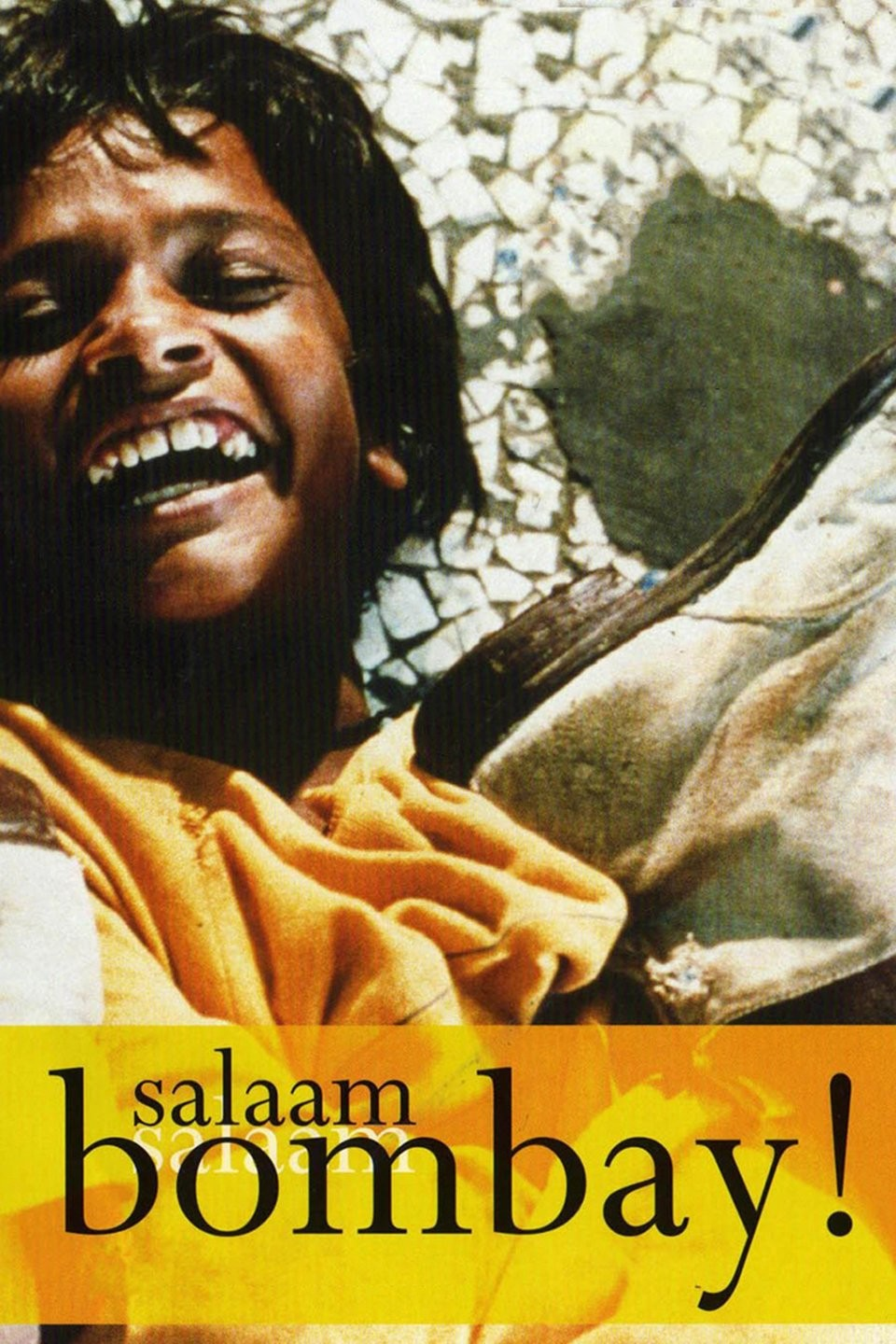

In 1988, Nair made her feature film debut with Salaam Bombay!—a film that would define her career and establish her as a major filmmaking force. Co-written with documentarian Sooni Taraporevala, the film follows Krishna, an eleven-year-old abandoned on the streets of Mumbai, navigating a harsh world of child labor, trafficking, and survival.

What made Salaam Bombay! revolutionary wasn't just its story—it was how Nair told it. She cast real street children, creating an atmosphere of raw authenticity that no actors could replicate. The film blended documentary realism with emotional depth, forcing audiences to witness poverty and resilience without the softness of conventional cinema.

The recognition was immediate and overwhelming. Salaam Bombay! won the Camera d'Or (best first feature) and Prix du Publique (most popular film) at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival. It became the second Indian film ever nominated for an Academy Award in the Best Foreign Language Film category. It earned BAFTA and Golden Globe nominations. And crucially, it proved that audiences worldwide wanted authentic, challenging stories from India.

But Nair didn't stop there. She did something extraordinary: she used the profits from Salaam Bombay! to establish the Salaam Baalak Trust in 1988, a nonprofit that provides shelter, education, healthcare, and vocational training to street and working children in Delhi and across India.

Mississippi Masala: Breaking Barriers, Crossing Borders

Three years after Salaam Bombay!, Nair returned with Mississippi Masala (1991), a film that defied easy categorization. The film told the story of an unlikely romance between Demetrius, an African-American carpet cleaner played by Denzel Washington, and Mina, the daughter of an Indian family exiled from Uganda, played by Sarita Choudhury. It was an interracial love story set against the American Deep South—ambitious, tender, and deeply political.

This wasn't the first time Nair had tackled such territory. She had met her second husband, political scientist Mahmood Mamdani, while researching in Uganda for this film. What emerged was a work that explored migration, displacement, racism, and the possibility of love across seemingly insurmountable differences.

Mississippi Masala won three awards at the Venice Film Festival, including Best Screenplay. It proved that Nair wasn't a one-hit wonder. She was a filmmaker with range, vision, and the courage to tell stories that mainstream cinema wouldn't touch.

Monsoon Wedding: The Global Breakthrough

If Salaam Bombay! established Nair's talent and Mississippi Masala proved her versatility, then Monsoon Wedding (2001) was her triumph. This film, about a chaotic Punjabi wedding in Delhi unfolding during monsoon season, became her most successful and beloved work.

Monsoon Wedding wasn't about poverty or struggle. It was about family drama, arranged marriages, generational conflict, and the beauty of Indian tradition meeting modern reality. The film featured an ensemble cast of acclaimed performers—Naseeruddin Shah, Rajat Kapoor, Lillete Dubey, Shefali Shah, and Vasundhara Das—creating a tapestry of interconnected storylines.

The film won the Golden Lion at the 2001 Venice Film Festival and was nominated for BAFTA, Golden Globe, and Critics' Choice awards. It became a commercial and critical sensation, proving that Indian stories could captivate global audiences. Nair's use of color, music, and visual storytelling created an infectious energy that made audiences feel the chaos, joy, and intimacy of a large Indian family navigating tradition and modernity.

Most importantly, Monsoon Wedding was adapted into a successful theatrical production that premiered at Berkeley Repertory Theatre in 2017, further extending Nair's artistic reach beyond cinema.

Literary Adaptations and International Storytelling

After Monsoon Wedding, Nair expanded her scope. She adapted William Makepeace Thackeray's Vanity Fair (2004) into a provocative period drama with Reese Witherspoon as the ambitious Becky Sharp. Then came The Namesake (2006), based on Jhumpa Lahiri's novel about Indian immigrants in America, exploring themes of cultural identity and generational conflict.

These adaptations showcased Nair's ability to work with existing literary material while maintaining her distinctive vision. She followed with Amelia (2009), a biopic about American aviator Amelia Earhart, and The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2012), a psychological thriller about a Pakistani man wrestling with his identity post-9/11.

Then in 2016, she directed Queen of Katwe, a film that brought her full circle—telling the inspiring true story of Phiona Mutesi, a Ugandan chess prodigy from extreme poverty who became a grandmaster. The film showcased Nair's signature blend of authenticity, hope, and stunning visual storytelling.

Beyond Film: Building East African Cinema

While her films garnered international acclaim, Nair was simultaneously building infrastructure for filmmaking in East Africa. In 2005, she established the Maisha Film Lab in Kampala, Uganda—a nonprofit training facility for emerging filmmakers and youth across East Africa.

The name Maisha means "life" in Swahili, and the lab's motto encapsulates Nair's philosophy: "If we don't tell our stories, no one else will." The facility offers hands-on training in screenwriting, directing, cinematography, editing, sound, and acting. It's not just a school—it's a movement to center African narratives in global cinema.

Notable Maisha alumni include celebrated actress Lupita Nyong'o, directors like Kivu Ruhorahoza and Joel Karekezi, and countless other East African filmmakers now creating powerful work. In 2018, Nair collaborated with award-winning architect Raul Pantaleo to design Maisha's permanent school building, featuring open classrooms overlooking Lake Victoria—a physical manifestation of her commitment to nurturing African talent.

Recent Projects: Adapting Stories, Shaping Culture

Nair's career has continued to evolve. In 2020, it was announced that she would adapt The Jungle Prince of Delhi—a Pulitzer Prize-nominated New York Times story by journalist Ellen Barry—into a limited series for Amazon Studios. The story explores the mysterious royal family of Oudh living in a ruined palace in Delhi, uncovering deeper truths about India's partition and displaced nobility.

In 2021, Disney+ announced that Nair would direct National Treasure: Edge of History, a reimagining of the National Treasure franchise with a new cast. Released in 2022, the series demonstrated her ability to work within studio franchises while maintaining her storytelling sensibility.

She also directed the acclaimed BBC adaptation of Vikram Seth's literary epic A Suitable Boy, which critics praised for its lush visual storytelling and faithful adaptation of the complex novel.

The Person Behind the Camera

Nair's personal life has shaped her art as profoundly as her career has shaped her identity. Her first marriage to photographer Mitch Epstein ended in 1987. Her second marriage to Mahmood Mamdani produced her son Zohran, born in 1991. That son has now made his own headlines—in November 2025, Zohran Mamdani was elected as New York City's first Muslim mayor, marking a historic moment that has drawn attention to his mother's decades of work as a visionary artist and activist.

As of 2015, Nair has lived in New York City, where she serves as an adjunct professor in the Film Division at Columbia University's School of Arts. This academic role allows her to mentor the next generation of filmmakers while continuing her own creative work. She practices yoga regularly—a discipline she often incorporates into her film sets, believing it centers the cast and crew.

Why Mira Nair Matters Now

In an era of streaming platforms and content saturation, Mira Nair's work stands out because it refuses easy categorization or commercial compromise. Her films are simultaneously commercial and artistic, globally accessible and culturally specific, entertaining and politically conscious.

She challenged India's censors over Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love (1996), eventually taking the battle to the Indian Supreme Court. She placed street children at the center of mainstream cinema when Bollywood was obsessed with glamour and escapism. She told interracial love stories before Hollywood was comfortable with them. She celebrated Indian weddings with infectious joy rather than exoticizing them.

Most crucially, she understood something fundamental: that telling stories about marginalized people isn't charity—it's necessary cinema. That celebrating cultural specificity doesn't limit a film's universal appeal—it enhances it. That a filmmaker's responsibility extends beyond the film set to the communities whose stories they tell.

The Legacy That Continues

As Mira Nair enters her seventh decade, her influence is undeniable. She's inspired generations of filmmakers—Indian, African, and international—to believe that their stories matter. Through Salaam Baalak Trust, she's directly transformed the lives of tens of thousands of vulnerable children. Through Maisha Film Lab, she's building the infrastructure for East African cinema to flourish.

Her body of work—from Salaam Bombay! to Queen of Katwe, from documentaries to literary adaptations—demonstrates a filmmaker in constant evolution, never repeating herself, always pushing toward more authentic, more humane, more necessary storytelling.

In an industry often obsessed with spectacle and franchise repetition, Mira Nair remains committed to the essential work: telling the stories that need to be told, giving voice to the voiceless, and believing that cinema can be both beautiful and transformative.

That's why she matters. That's why her films endure. And that's why a new generation—discovering her work through streaming platforms, film festivals, and yes, through her son's historic election—will continue to be changed by her vision.

Her motto, borrowed from Maisha Film Lab, says it best: "If we don't tell our stories, no one else will." Mira Nair has spent her career proving that these stories deserve to be told—and that the world needs them.